Nuclear weapons education has disappeared, it’s time to change that

If we are serious about wanting to diversify and expand the field, then we must start educating our students much earlier.

For twenty years I have walked into a college classroom this week to introduce myself to students as their professor. For those same twenty years, every time I asked students if they have ever read John Hersey’s Hiroshima or learned about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the answer has historically been “no.” I grew to accept that when it came to teaching about nuclear weapons and disarmament, I am most likely starting from scratch. How and why does this continue to happen and how can we change it?

There are many reasons why disarmament education is not taught in schools at any age. The first happens quite early in a students’ education, which is the siloing of the humanities and STEM fields.

Did not Albert Einstein, Leonardo DaVinci, and other great minds in history appreciate and see the value in both the humanities and physical sciences?

Students often have to choose a lane: either study creative writing, music, art, history, philosophy, and literature or physics, chemistry, math, and computer science. Why would we not want our students to study both? If a student is studying physics wouldn’t it be a good thing to also have them study ethics or history? Did not Albert Einstein, Leonardo DaVinci, and other great minds in history appreciate and see the value in both the humanities and physical sciences?

Help us relaunch the magazine for nuclear disarmament.

Many organizations in the arms control and disarmament space have created valuable resources for students and the general public to learn about the nuclear threat. Therefore, the problem isn’t a lack of resources. The issue lies in distribution. Many educators simply do not know these resources exist, where to find them, or how to incorporate them into their already jammed curriculum, often dictated to them by the state and district in which they teach.

To that degree, if we are serious about teaching disarmament education, then we must meet educators and students where they are. For teachers, who are already spread too thin and often are mandated to teach a specific curriculum, we cannot expect them to create new lesson plans, units, and materials focused on nuclear disarmament. What we can do is help them to incorporate the issue into their existing lessons.

For example, if students are learning about the history of jazz in a music course, one can use that time to teach about John Coltrane’s tour in in Japan, his insistence on playing in Nagasaki, and the piece he wrote about the atomic bombings and the need for peace. Teachers could show their class Charlie Parker’s statements about nuclear weapons and how he promoted the Ban the Bomb pledge in the early 1950s.

A literature teacher who has their students reading A Raisin in the Sun could use that time to also discuss Lorraine Hansberry’s antinuclear stance and her last play about two lone survivors of nuclear war.

By the time students start college, majors are determined, career paths have begun. This is why it is so important that we start much earlier in educating our youth about nuclear disarmament. When it comes to younger students, we have figured out how to teach about difficult subjects such as the Holocaust and Transatlantic Slave Trade. However, we have not done this when it comes to disarmament. We need to create materials best suited for younger students and assess what is too much or too little for them to handle. We need to examine educating based on fear and hope.

Students also need to see themselves in this history. Students will often try to find someone who looks like them, shares a common ancestry, or some other trait that they can relate to. However, if Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, and Indigenous students do not see themselves in this history, how can we expect them to want to pursue a career in disarmament or work to eliminate nuclear weapons?

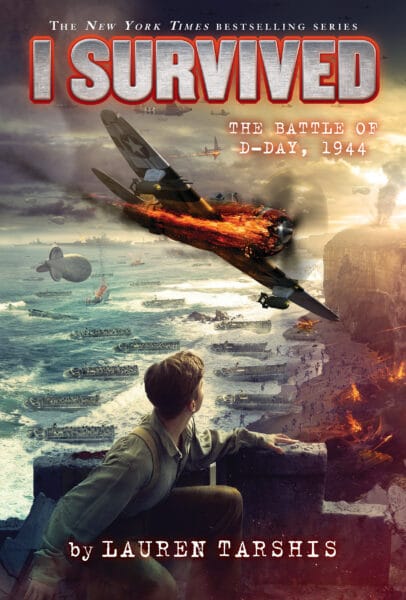

The popular I Survived series has books on the D-Day, but no titles about the atomic bombings or nuclear testing.

While we cannot expect every student to pursue a career in the nuclear space, that doesn’t mean they should not learn about nuclear disarmament. If each student learned about the nuclear issue they would hopefully take that knowledge and empathy to the various industries they are working in, and who knows how many that would affect from decisions that are made in the boardrooms to "water cooler" conversations (or with your own water bottle), to spearheading new ideas. This is how we ended up with Architects for Social Responsibility, Business Executives Move, Dancers for Disarmament, Life Insurance Industry Committee for a Nuclear Weapons Freeze, Parenting in a Nuclear Age, Performing Artists for Nuclear Disarmament, Athletes United for Peace, Social Workers for Nuclear Disarmament, the Nurses Alliance for the Prevention of Nuclear War, and Physicians for Social Responsibility.

If we are serious about wanting to diversify and expand the field, then we must start educating our students much earlier. We will never be able to achieve this if the only way one can learn about this issue and be offered a seat at the table is if they have studied at an elite private institution in Monterey, California.

Throughout this series we will review and assess materials already available and offer suggestions as to how we can ensure these resources get into the hands of educators, parents, and students. Our mission is to create a more educated public and to once again build a movement that will demand we eliminate these weapons once and for all.

Sign up for Email updates to stay informed when new materials for educators drop.