Director Jeff Daniels Unfiltered

The Television Event director on what drove him to make a documentary about a legendary TV movie.

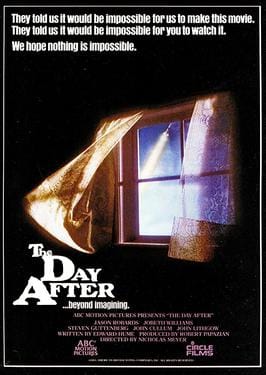

In 1983, a 100 million people, nearly 70% of the viewing population in the U.S. watched the same movie together — about nuclear war. The director of Television Event discusses with Nuclear Times what he learned about The Day After, it's impact on the nuclear arms race, and reflects on a time when people with opposing views did something radical by today's standards: talked to one another.

Vincent Intondi: What was your motivation to take on this project?

Jeff Daniels: I think that there are a number of reasons. When you watch something like The Day After when you're 5, and my family was not nuts, they did put me to bed before anything got really hairy, but the point is that all these people you're being introduced to are going to die a slow, horrible death. That hits you at 5 years old, and it's a topic of conversation families were having. And kids hear this so, I think that sticks with you in a certain way where a number of history teachers that I've had over the years have called me the Reagan baby generation, where we have this healthy distrust in adults. I think that was part of it, and then you start asking yourself how do these things get made as an independent documentary filmmaker, 75% of your job is trying to get funding and convincing people to be involved in your work so when the people who put money into your work are involved, you're very aware of that, and so hearing the inside story on The Day After, and how someone like Nicholas Meyer, this Hollywood director had to butt heads with network executives who were in the editing room—that's all I had to hear.

Help us relaunch the magazine for nuclear disarmament.

But I'm also someone who now has a kid. My friends are of the generation where they're having kids who are asking questions. That seems similar to what I was going through when I was growing up in the 80s asking how can you do this to us, and our future, in terms of how you are flagrantly disregarding clear evidence of a climate crisis? You’re complicit in this. What are you doing about this? It all seemed way too familiar, so I thought, what a great way to try and look at a period in American history when we were polarized politically and when a piece of art as simple as a TV movie of the week was able to hit people in a way where they were talking together despite their differences of opinion. I needed to be reminded of that. I felt others may lock into it too, and because there was a compelling story in it, maybe that's a way of getting them to think about things that they'd rather not.

It seems like it's fear-mongering? Well so is threatening people with nuclear weapons.

Vin: There are two things that you mentioned that I want to touch on. Nick [Meyer] was very clear that he didn't like Reagan, that he had an objective of getting him out of office and then there was this whole issue of it can't be about politics—we can't mention who launched the nuclear weapon. The villain is the nuclear weapon, and we just need to show what happened. And I'm very conflicted on that, because part of me thinks that if you don't bring the politics in aren't you then also making a statement or taking a side? At the same time, I also understand the argument of if you bring politics in, do you lose the audience? What are your thoughts on how we handle politics? Do you think it's the right thing to do to just leave politics out? Is it even possible?

Jeff: You can't avoid the issue of politics, especially when you're involved in the arts on any level. You're always going to get political in some way, and what does it mean to get political? A film like The Day After was really good in trying to dissect that question because in order for it to work on commercial television, where the point is to get as many people viewing as possible, you need to cast a wide net. What does that look like? In one way, trying to not be political, whatever that means, in this case, not showing who pressed the button first gets to a bigger point. Where people aren't distracted by something that may make them think is another lefty Hollywood tirade. That could turn people off. And for commercial television, especially in 1983, it was very important for that industry cast that wide net.

Follow Nuclear Times on Bluesky

Luckily, you had a writer in The Day After who was very much against what the Reagan administration was doing. But he knew as a writer that if he just focused on the facts and show people what surviving nuclear war actually looked like then people can make up their own mind, and it really doesn't matter what kind of political leaning they came from and it will be harder to attack the film for that reason. And I just thought, what a great case study. To look at the making of The Day After and show how one tries to remain apolitical so that you're able to allow people to feel something that is different from what everyone else is talking about, especially with nuclear war. It's easy to politicize if it can be used as a weapon or a threat. So, let's just kind of step back, and that's where the arts come in and says, let's just look at this on an emotional level. What would it look like? How to prevent it, that's up to you. That's your decision. This is why the panel discussion after The Day After really hit me. To speak with people who had experienced a type of genocide, where you have people dying en masse, and it seems unthinkable. Why would anyone do that? That seems so inhuman. Well, it did happen. It can happen and is happening.

So, I think that allowing the arts to make us think emotionally allows us to get away from something that is undeniably political, but it's an equivocator. Everyone is feeling that they do not want to live in a world where nuclear war is possible and has happened so what are we going do about it? And that galvanizes people, and they then act politically. So, I think that the case study of The Day After to see how one can make something that allows you to feel emotionally about an issue that it's hard to talk about that politically may not be talked about in terms of what would happen, because it seems like it's fear-mongering? Well so is threatening people with nuclear weapons. I think that shows the importance of the arts on any level. It's a great galvanizing experience. It gets straight to our humanity by entering into that emotional element to get beyond military strategy or all these other elements that deny a very human part. An element of the conversation that we're not having and I think that The Day After took advantage of that situation, and understanding that this is how it works and it is worth learning, especially today.

I think that we all know behind that we're not really picking a side. The side we're picking is humanity.

Vin: I'd like to focus on art and the artists’ role. I hate that art is often looked at as an appendage to movements. Art has always been so central, not just to this movement, but many social movements. There was a debate among artists during the Harlem Renaissance which asked the question of if you are an artist, how should you use that art? You are blessed with these gifts. Should you use that art to push for social justice and racial equality? Others said, no, if I just want to paint butterflies, let me just paint butterflies. Why do I have to be using my gifts for this? Where do you stand on the role of the artist?

Jeff: I think it's so vital, and I understand that some artists understand the power that the arts can have in allowing us to consider the things that are very difficult and for that reason, I can understand why some artists want to push a certain agenda that they have, because were illustrating a very chaotic world emotionally. How in the world do you do that? How can you say that you don't care? I don't blame artists for championing a certain issue or taking a certain side, but I think that we all know behind that we're not really picking a side. The side we're picking is humanity. We're allowing a different element of what makes us human to be part of the calculation of what we think about, what's going on. And it gets us out of the pattern of we're not going to listen to our brother, because he's crazy, and I don't know what my daughter's talking about, the things that they're learning at school. That can be alienating, but when you are all watching the same thing and having an emotional reaction to that, you may start talking together. You're recognizing the same thing. And you may not feel as alone. The arts provide us the ability to come together despite our differences so that we don't feel like we're crazy. Like, you feel it too, don't you? You may have a different way of trying to solve the problem, but I'm not alone here, right? Like, I'm not nuts. I think that that's extremely important for us, and has been the role of the arts forever. I think it's quite essential, and artists understand that power. Some can manipulate it but in the end we're basically trying to communicate something that is quite human, so that we can in the case of nuclear war, imagine the unimaginable. And that is something that allows us to be human at our best and worst.

Vin: There is the other side, which is very difficult for artists and why I admire you all so much. There can be a price to pay for taking that stand and saying, I'm going to use my art to shine a light on Gaza, for nuclear disarmament, for racial equality. Funding is already so difficult for the arts and to take that stand could be the death knell for artists, so I understand that as well. That said, was it more difficult to get the funding to put this together?

Jeff: Documentary filmmakers often ask, is this what broadcasters and distributors want or what I want to make? Should I just make it myself? I'm making films that I feel are important to me are not heard enough. So, I have this uphill battle of trying to get funding for projects that may not be seen as widely as some of the others. I feel like I'm giving people what they need in a form that is compelling. Then people ask questions about my intentions and where my funding comes from. Is it government funding? Is it philanthropic funding? Is it individual investors from those who may agree with a certain point of view? So, I have to navigate quite a lot, and I feel that is why it's important for me to focus on subjects that are taking a broader look. I made a film called Mother with a Gun that was about the leader of a militant Jewish organization based in Los Angeles that had an incredible history in New York, and it was a film about violence and how that can tear a family apart and how people try and justify violence by calling it self-defense. And, what a quagmire to get into. I felt that even though I didn't agree with the way in which this organization was trying to defend the Jewish community, I found that a lot of people who wanted to fund the film were asking, where do you stand on this? The insinuation can be there, and so that can make it really difficult to try and fund some of these projects.

They were calling this a health issue. This is something that affects human beings.

I enjoyed the process of trying to fund Television Event because I was able to get to the people who, in the early 70s and 80s, the 60s and 50s before then were protesting together, not as the left or the right. They were calling this a health issue. This is something that affects human beings. This is a problem we both recognize is here and we can't argue with the science. What are we going to do about this? How do we use our democratic process to work together to find something that addresses a problem we all agree exists? So, I think by emphasizing the problem, and showing the discourse that can happen so that change can actually be made is where I stand with the films that I make, and I believe that really, at the heart, is what a lot of other filmmakers and artists who claim to be political are doing. They don't want to ignore half of their audience. They want everyone to be involved, and are just trying to find a way to get them in without compromising their vision and the facts. That's the job. That's the art, the craft.

Vin: Let's talk a little bit about where they had the film was set. Kansas has such a history. We can go all the way back to Bleeding Kansas with the Civil War. You also had Athletes United for Peace who were having races with Russian athletes leading up to this in Kansas. I thought it was a brilliant move to set it in middle America, especially with the politics. Do you think it would have had a different response had the bomb been dropped in a major city?

Jeff: I think it's kind of a beautiful journey to choose Lawrence, Kansas this small city directly in the center of the United States as the setting for The Day After. To research for The Day After, Ed Hume used a government report on what the actual effects of a nuclear war would be. For the report, the government chose a small college town to give an example of the moment-by-moment story of what a nuclear attack would do and how they'd react, and how many people would die, how to get food to the area and help, how long things would last. So, this was down to the government level. They were thinking well, a college town is probably the best way for us to have a scientific understanding of what the effects of a nuclear war would be. Ed Hume read that because he wanted to make sure the project was as well-researched, as did all members of the film from Nicholas Meyer to Stephanie Austin. They looked at the science behind this. Producer Bob Papazian's uncle was one of the scientists who was able to explain the idea of an electromagnetic pulse which was shown in that film. It was one of the first representations of bursting a bomb in the air and shutting down old analog machines. With Lawrence, you can avoid the questions of is it left-leaning or right-leaning. That’s not the point. It’s the middle of America. We can all relate to that. That's something that has meaning, whether you're from a city or a small town. So, I thought that that it was quite beautiful that all of the research from the government to the studio knew that looking at the middle of America was the best way to cast a wider net and show everyone something so that they could start talking together about it. And seeing how it affected the people of Lawrence, Kansas was something I had to ask about.

Vin: Can I ask you about the actor who played Airman McCoy? He’s not only one of the few Black characters in this film, but his character comes off kind of as the moral compass of the whole story. Was there a conscious decision to cast an African American actor in this role? How much did they want to feature the McCloy character?

Jeff: There are a few missed opportunities for me in the film to point out just how diverse the cast and crew of The Day After. Was. I think a main part of that is because this project offered people who work in Hollywood an opportunity to make something with meaning and that attracts all people so in some ways, naturally, they were able to get a diverse group of people who were desperate to work on this film and add the understanding of the shared fear that they have of what a world after the button was pressed would look like. I think that there was an intention with the network ABC, and the president of ABC Entertainment, Brandon Stoddard, who had just made the most-watched thing on television ever, Roots. So, I think that he understood the importance of having a diverse cast shown on television, because this was for an American audience and you recognize that and cast a wide net. You want all Americans to watch this and to connect with it in some way. So, I think that was what Ed Hume wanted as well. He's an incredible writer who wrote some of the best television series that we've had in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. I think the diversity of the films’ cast and crew was something that was ongoing and very appropriate for a film that is trying to galvanize what was then a very polarized country politically and culturally, and in many ways. It was great to see that diversity of experience and I think there are a number of reasons why certain characters may have been the moral compass, for one reason or another. They were very mindful of that and having a diverse cast was intentional, but it was also quite natural. It wasn't something that was shoehorned in to check a diversity box. It was a very direct, intentional decision that helped the narrative and helped tell a broad story to the widest possible audience.

Vin: What was one of the things in your research that surprised you the most about The Day After?

Jeff: I think it was really fun for me to see how the Reagan administration tried to tear down the integrity of the film. And because the film was based on government documents the Reagan administration thought we can't poke holes through this because it's extremely well researched. And what they're showing is essentially the same research that we've collected. It's actually the exact same. Materials that we've collected about electromagnetic pulses and nuclear winter. So, because of that, they saw it as a threat, and they kind of moved with it and said well if we can't put it down and tear it apart, let's use it and say of course this is exactly what we're trying to prevent. And the only way to prevent that is through strength and having a bigger stick, so vote for us in the next election, and that's exactly what happened. They won in a landslide. So, I think, seeing that was interesting to me, just how the Reagan administration was able to use it in a way to their benefit, because they understood the power that television had as a mass medium, and a president like Ronald Reagan, who was an actor and absolutely understood the power of the medium treated it with the attention it needed. That was fascinating and one of the main reasons I wanted to make the film.

Vin: Was The Day After screened in other countries? What was the international response to it?

And it showed the world that America has the ability to look at itself critically. I think the rest of the world needed to see that at a time when it's loudest representatives were threatening them with nuclear war.

Jeff: I think to see a country so polarized then come out with a film that shows the effects of nuclear war, something that the current administration was threatening on the only other superpower was something the world was listening to. So, to see a nation that's so polarized politically and saber-rattling in a way where they're threatening the world with nuclear weapons and then ABC, the family-friendly network that makes Happy Days and the Love Boat is going to show what nuclear war looks like on television to Americans, and it was the most watched TV movie of all time, the rest of the world paid attention to that. That was a huge story internationally. I live in Melbourne, Australia. A lot of that footage was shot by the Australian Broadcasting, corporation, ABC. It was a news story throughout the world, that this TV movie was being made in the first place, let alone how. How widely watched it was, and how Lawrence, Kansas actually put on a vigil for the people in this fictional film who died. That was broadcast live and The Day After was shown in scores of countries. It was dubbed over in tons of different languages. It was the first television movie to be, I believe, broadcast on Soviet television in 1987. And it showed the world that America has the ability to look at itself critically. I think the rest of the world needed to see that at a time when it's loudest representatives were threatening them with nuclear war.

Vin: Could we ever remake The Day After today and what would that look like? How would social media handle something like this? What would the special effects be? Could it even find a distributor with the politics of today? We know Annie Jacobson's book's, Nuclear War, is going to be made for the big screen and James Cameron is making his film about Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What do you think will happen? Sadly, I don't even think the panel discussion that aired following The Day After could happen today. I see Ted Koppel, and William F. Buckley, Carl Sagan, and I think today it would just turn into a screaming match. It would be a mess on CNN. What do you think?

Jeff: I think it's Interesting how we have more options than ever to communicate with each other and yet that has made it harder than ever for us to speak collectively to each other at the same time. So, in a way, we're kind of just talking to our friends, and we're creating these bubbles. We're only speaking to each other and speaking about the other people, instead of with them. So, it is ironic that technology allows us to be connected more than ever but also provides easy opportunities for us to just talk only with those who agree with us. I think that's dangerous, and that's what makes it very difficult for us to make something that like The Day After, in 1983, that could have that kind of impact. Ted Koppel explained to me that we probably had the best opportunity for democracy at that time, because people were gaining the same information, and they were able to talk about the same piece of information. And then think critically about that. And to hear, in one outlet from people of opposing viewpoints what they thought about that issue so people were hearing both sides to a degree. They were hearing a human side, someone who doesn't care about numbers or politics. Having galvanizing moments like we did back in 1983, I think that the opportunity for those galvanizing moments is possible and that we are trying to find ways to make that happen so that we can speak to each other on a mass level, and get to the truth. I think people want to know that what they're seeing is something that is fact based. I think that people are attracted to that, and that people want that, and I think that won't ever really go away, and that creative people will be able to harness the internet in a way where they'll say, this needs curation. This needs fact-checking on a level where people know, they can rely on us. And once we have that then we have the big audiences that we need to talk about the things we would rather not. In a way that allows people to make up their own minds. I think that's possible, and so by visiting a period where that happened and we did come together, and talked to each other as a family, and then went away and voted for Reagan again, or voted for the other people. They were talking to each other, families weren't separating. That is possible, as it's within our capacity. So, we must find ways to harness this incredible gift of the internet to make that happen again.

Vin: Since this film was released, have you been attacked by the pro-nuclear and deterrence side? Have you faced any backlash?

Jeff: It's all been positive. I think that trying to focus on the conversation that was had and how artists were attacked for being this way or that politically, and making that part of the film woke people up to say, ah, that is how it works. And how was Reagan shown here? Was he a joke, or was he actually someone who, by talking with instead of about Soviet Russia was able to bring about a meaningful reduction in nuclear weapons. I think that there's enough in the film that allows people, regardless of their political leaning, to see themselves represented in a way where change is made, because their voices are heard, and they're talking with each other instead of about each other. I'm so proud of that. I'm so glad that that allows people, especially now, when it seems like we're bombarded with information that is hard to digest or fact-check, and it leads to alienation and depression. You don't want to talk to anyone about it, you don't even want to read the news. I think that what people are getting out of this film is a reminder of what is possible, of how we actually are able to talk to each other despite our differences, and organizations like Rotary, which are community building and apolitical. For a reason, and organizations that still focus on the health threats that nuclear weapons pose regardless of whether you're using them or not, or building them, they're undeniable facts that I think, the nuclear discussion around nuclear weapons can be quite galvanizing, and it can bring people together. I think documenting that period shows that we're able to have that same discussion now. It certainly makes me feel better, and it seems like the audiences are feeling the same way after they watch Television Event.

Vin: Have you heard from individuals who watched Television Event and gone on to tell you about their memories of watching The Day After live in 1983?

Jeff: It's been a great way for Gen X to say, this is how it was for us. This is something that we went through. It's reminding them, oh yeah, I do remember that. I don't remember being scared about nuclear war, or if I did, I certainly didn't want to think about it, which is usually the case. Allowing them to remember this period where network television made them think about something they'd rather not and talking about that with their kids, and with the next generation I think has been a really great opportunity for this kind of intergenerational discussion on how do we talk about these things? Parents have the opportunity to tell their kids about a time when the whole family came together to watch this film. When everyone in their college dorm went into the common room to watch this film, and talk about it, and for people in their homes to relate to what people were doing in the street protesting. Whether they agreed with them or not, they understood the fear. I'm in touch with that. I think that this is a great opportunity for Gen X to share that story. And to be reminded of a time when America again was very polarized politically in a way and where they realize they tried to do this to us in the 80s, and then this film kind of put things in perspective. I think it's vital to remember that and that's part of the conversation I'm getting from viewers as they watch Television Event. I'm so glad that it's finally picking up. It's hard for these films to get out there, to get a theatrical release but it's no wonder that people are enjoying the experience of watching this film. Many are remembering a time when things were very, very difficult politically and yet they were still able to talk with each other. What an incredibly important thing to know, to be reminded of, and to share with the next generation.

Vin: Thank you Jeff for your time and making the film.

Jeff: Thank you so much, Vincent. It's my pleasure to be a part of this.

Find screenings and learn more about Television Event here.